Technology is changing the nature of work as we know it. Our People Profession 2030 report identified digital and technological transformation as one of five key trends that will influence the future world of work. As part of our Latest insights series, this article explores how people professionals can use their expertise to take a prominent role in technological-driven change to benefit organisations and their employees.

Technology is changing the nature of work as we know it. Our People Profession 2030 report identified digital and technological transformation as one of five key trends that will influence the future world of work. As part of our Latest insights series, this article explores how people professionals can use their expertise to take a prominent role in technological-driven change to benefit organisations and their employees.

It’s not just routine physical tasks that are increasingly being automated, but also routine mental work. Automation is happening at different rates in different jobs and industries around the world. While drone delivery is being trialled in the UK, some Chinese companies have been using them to deliver items to customers in hard to reach rural areas since before 2017. Driverless vehicles are being used in controlled areas such as airports and metro lines. Price comparison sites promoted by furry animals and other eccentric characters have simplified the mental task of choosing insurance, replacing the role of many insurance brokers. HR payroll software automates routine payroll activities and can even allow employees to request wages outside the normal payroll cycle through an app.

Within the next few decades it is possible all routine physical and mental tasks could eventually be done more cheaply by machines. How? Technology improves productivity by reducing the time and cost of production, which in turn fuels demand and creates jobs. But further productivity improvements can eliminate jobs.

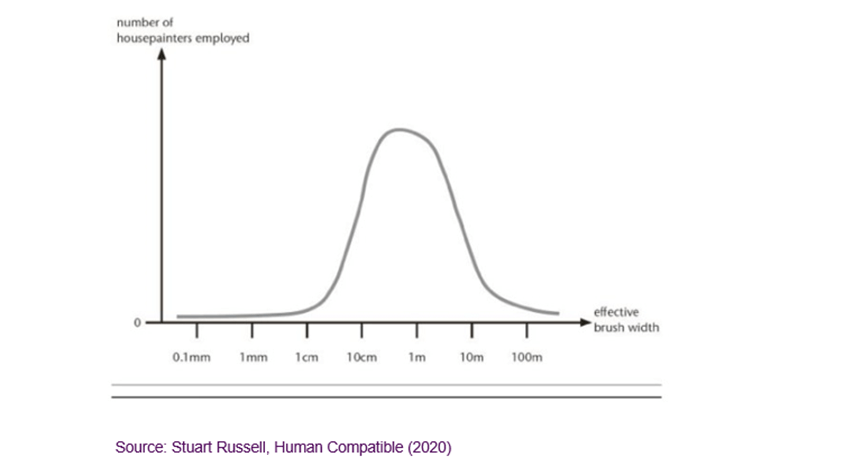

In his book Human Compatible, AI expert Professor Stuart Russell uses house painting as an example to explain this (see Figure 1). The hypothetical graph shows house painting employment as technology improves. Paintbrush width represents the level of automation. If brushes are the width of one hair, no house painters are employed. At one millimetre wide, a few painters might be employed to paint the homes of the wealthy. When brushes are 10 centimetres wide, most homeowners can afford to have their houses painted, creating thousands of house painter jobs. Demand for house painting peaks when large areas can be painted with rollers and spray guns, so the number of house painter jobs start to fall. Once one person can manage a team of house- painting robots, there will be fewer house painting jobs for people. Imagine this curve being applied to all routine jobs.

Figure 1: Technology creates jobs but further improvements in productivity eliminate jobs

For the next few years at least, the evidence suggests that technology will continue to create more jobs than it destroys. By 2025, the World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates machines will create 97 million jobs for humans and replace 85 million. But the rate that new jobs replace redundant jobs is expected to slow down in 2025. The WEF’s Future of Jobs Report 2020 doesn’t predict the extent to which the new jobs will provide enough income or be accessible to displaced employees. McKinsey predicts between 400 million to 800 million people could be displaced by automation and need to find new jobs by 2030. Although estimates vary widely, it is clear that millions of employees will need to learn new skills.

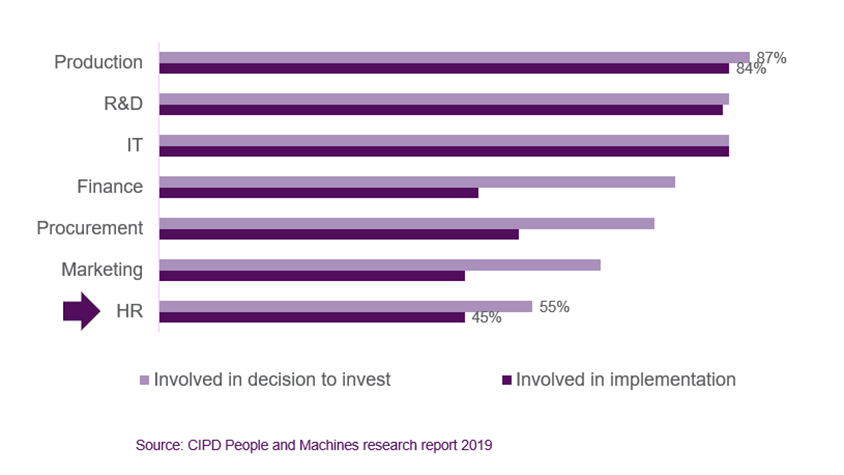

The CIPD People and machines survey highlighted that the people profession is more likely to be involved in the decision to invest in AI and automation or its implementation when roles are created or eliminated (Figure 2). But in general, HR is less likely to be involved in technology investment decisions or implementation than other departments (Figure 3).

Figure 2: HR involvement in decisions around AI and automation investment and implementation

Figure 3: Departments involved in decision to invest and implementation of AI and automation

People professionals have a responsibility to address the many nuances associated with digital transformation and its impact on people. How can the profession be more involved in shaping this change?

Conducting workforce planning and skills gap analysis

There is, of course, more to the employee lifecycle than being recruited to or leaving a role. Employees need to be onboarded, developed and motivated to perform to their best. People professionals can take a more proactive role in workforce planning and skills gap analysis if they are included early in decisions involving investment in technology. For example, by:

- considering how internal and external trends might impact the organisation’s future workforce needs and skills gaps

- working with leaders to identify strategies to meet the organisation’s future workforce needs

- facilitating early conversations with employees who might be affected by new technology.

Employees who are consulted are more likely to agree with the business benefits of technology and feel more confident to raise concerns, according to the CIPD Workplace technology: employee experience report.

Considering job redesign, incentives and other ways to improve job quality

When technology impacts work, people professionals should consider how the CIPD’s seven dimensions of job quality can be leveraged to improve overall job quality. The seven dimensions include:

- pay and benefits

- employment contracts

- work-life balance

- job design and nature of work

- relationships at work

- employee voice

- health and wellbeing

Implemented correctly, technology can improve both employee performance and job quality. Approached the wrong way, it can have the opposite effect.

Explore with managers and affected employees how intelligent process automation can redesign, and potentially safeguard, their jobs. If some of the more tedious parts of a job can be automated, this can help give back time to focus on higher value tasks. Technology can help the people profession conduct this process efficiently to gain insight on employees’ current skills. For example, by using a talent management system if information on skills across the organisation is regularly updated, or using LinkedIn or similar social media platforms.

Consider ways to incentivise the workforce to use technology to automate their work to benefit themselves and the organisation. For example, employees who have automated a significant amount of work might be rewarded with a four-day week, attend expensive training, or receive bonuses. These employees could become automation internal coaches or even sell their consultancy services to other organisations. Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) did the latter after enterprise-wide automation eliminated 800 full-time roles. Headcount did not fall. Instead SMBC retrained and transferred displaced employees to its new subsidiary SMBC Value Creation. The subsidiary offers intelligent process automation expertise to other financial institutions.

Intelligent Automation authors Bornet, Barkin and Wirtz believe that incentivising automation could avoid moral dilemmas such as the one highlighted by this viral Stack Exchange post: ‘Is it unethical for me not to tell my employer I’ve automated my job?’. After 18 months in the role, the employee had automated their work to the point where they received full-time pay for work that now took only one or two hours a week.

Providing outplacement services, if necessary, working with government and other agencies

As noted in Figure 1, technology can eliminate jobs. Sometimes there are no alternative roles for employees in the organisation. In these situations, the people profession can organise outplacement services to give redundant employees the emotional and practical support they need to find jobs elsewhere.

In Kenya, Unilever’s tea plantations identified that mechanisation would impact low-skilled employees and families who depend on their livelihoods. Partnering with local government and non-governmental agencies, reskilling initiatives were deployed as well as a funding programme for employees to become entrepreneurs. Over 2,000 redundant employees are consequently in alternative employment. That’s over 10,000 livelihoods sustained. Trade unions and social partners said the initiatives have had a positive social impact in the community.

Participating in the debate on the future of work

The impact of technology on the future of work is too important for organisations to deal with internally. As we’ve seen in the Unilever example, governments and other agencies must also be involved when technology impacts the livelihoods of thousands of people. Otherwise, there could be social unrest. People professionals can draw on first-hand experiences from the ground to shape debates on the future work.

Skills, job design and wealth sharing are often key features of debate around the future of work:

- What skills do employees need for the future and what support do they need to gain those skills?

- How can jobs be designed to make working lives better?

- How do we share the financial gains of technology fairly to mitigate the risk of low-paid or redundant employees plunging into poverty?

Addressing these questions will involve refocusing education and societal values:

- If all mental and physical tasks can eventually be done more cheaply by machines, then shouldn’t education focus more on soft skills that are difficult to automate like empathy, creativity, and imagination?

- How do we use technology to create a people-centred jobs market that focuses more on enabling social and environmental change that benefits everyone?

Technology is changing the nature of work as we know it. But what happens in the future will depend on how governments, organisations and employees around the world respond. People professionals should play a key role in this response.

Get involved and help us understand the future of the profession

The

Profession Map

The international standard for all HR, L&D, OD and all other people professionals

Connect

and learn

We offer a range of ways to stay connected,from events to networking, workshops and webinars.

About the author

Hayfa Mohdzaini, Senior Research Adviser | Interim Head of Research

Hayfa joined us in 2020. Hayfa has degrees in computer science and human resources from University of York and University of Warwick respectively.

She started her career in the private sector working in IT and then HR and has been writing for the HR community since 2012. Previously she worked for another membership organisation (UCEA) where she expanded the range of pay and workforce benchmarking data available to the higher education HR community.

She is interested in how the people profession can contribute to good work through technology and has written several publications on our behalf, as well as judging our people management awards, speaking at conferences and exhibitions and providing commentary to the media on the subjects of people and technology.

An exploration of how generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be used effectively to support human resource management

Researchers investigate the daily obstacles faced by HR practitioners when trying to work proactively rather than reactively

Understand the principles of shared services, how they work, and the benefits they can bring to an organisation

Insight into how global issues are impacting people professionals in the UK, Ireland, Asia-Pacific, MENA and Canada

Peter Cheese, the CIPD's chief executive, looks at the challenges and opportunities faced by today’s business leaders and the strategic priorities needed to drive future success

We outline the key pieces of legislation set to come into force in the UK and explain their implications for employers and employees

We examine people’s desired hours and how this compares to the hours they actually work

Employers’ reactions to pension proposal highlight concerns over cost, while the CIPD calls for focus on raising pension awareness among staff, the need for higher contributions and better understanding of value for money